Document Text |

Summary |

| Island Hospital, Harper’s Ferry, VA. | |

| March 11, 1865 | |

| My dear Mother, | |

| You see I write to you very often and so keep you posted up as to what we are doing. Tonight I am rather lonely. Mrs. de Grindle being very unwell the other two young ladies are over in their wards. So I am quite alone for a little while. | I am lonely tonight. Mrs. De Grindle is sick, and the other girls who live here are working at the hospital. |

| There is hardly a day passed but what there is a death here sometimes several. One poor fellow died yesterday, such a handsome, bright boy. Apparently with the strongest of constitutions. That dreadful fever typhoid and pneumonia takes off so many of the poor fellows. | Every day a soldier dies at the hospital. Sometimes many die in one day. Yesterday a handsome, bright soldier died even though he had a strong body. The poor soldiers are being killed by diseases like typhoid and pneumonia. |

| I cannot tell you how thankful I am to be able to relieve the poor fellows. You must try and feel so too and be glad that I was formed for some use in this world. . . . | I am so glad I can help these poor soldiers. You must try and be glad too. . . . |

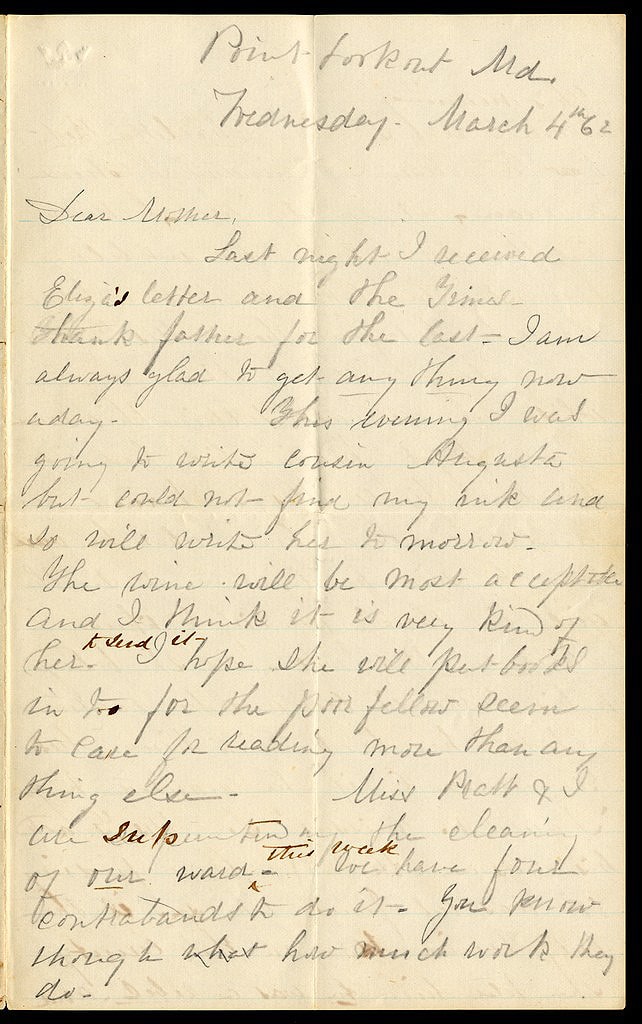

Letter home from Sarah Blunt written from Point Lookout, transcription, Maryland, May 11, 1863. New-York Historical Society Library.

Document Text |

| The first thing I met was a regiment of the vilest odors that ever assaulted the human nose, and took it by storm. Cologne, with its seven and seventy evil savors, was a posy-bed to it; and the worst of this affliction was, every one had assured me that it was a chronic weakness of all hospitals, and I must bear it. I did, armed with lavender water, with which I so besprinkled myself and premises, that, like my friend Sairy, I was soon known among my patients as “the nurse with the bottle.” Having been run over by three excited surgeons, bumped against by migratory coal-hods, water-pails, and small boys, nearly scalded by an avalanche of newly-filled tea-pots, and hopelessly entangled in a knot of colored sisters coming to wash, I progressed by slow stages up stairs and down, till the main hall was reached, and I paused to take breath and a survey. There they were! “Our brave boys,” as the papers justly call them, for cowards could hardly have been so riddled with shot and shell, so torn and shattered, nor have borne suffering for which we have no name, with an uncomplaining fortitude, which made one glad to cherish each as a brother. In they came, some on stretchers, some in men’s arms, some feebly staggering along propped on rude crutches, and one lay stark and still with covered face, as a comrade gave his name to be recorded before they carried him away to the dead house. All was hurry and confusion; the hall was full of these wrecks of humanity, for the most exhausted could not reach a bed till duly ticketed and registered; the walls were lined with rows of such as could sit, the floor covered with the more disabled, the steps and door-ways filled with helpers and lookers on; the sound of many feet and voices made that usually quiet hour as noisy as noon; and, in the midst of it all, the matron’s motherly face brought more comfort to many a poor soul, than the cordial draughts she administered, or the cheery words that welcomed all, making of the hospital a home. |

| The sight of several stretchers, each with its legless, armless, or desperately wounded occupant, entering my ward, admonished me that I was there to work, not to wonder or weep; so I corked up my feelings, and returned to the path of duty, which was rather “a hard road to travel” just then. The house had been a hotel before hospitals were needed, and many of the doors still bore their old names; some not so inappropriate as might be imagined, for my ward was in truth a ball-room, if gun-shot wounds could christen it. Forty beds were prepared, many already tenanted by tired men who fell down anywhere, and drowsed till the smell of food roused them. Round the great stove was gathered the dreariest group I ever saw—ragged, gaunt and pale, mud to the knees, with bloody bandages untouched since put on days before; many bundled up in blankets, coats being lost or useless; and all wearing that disheartened look which proclaimed defeat, more plainly than any telegram of the Burnside blunder. I pitied them so much, I dared not speak to them, though, remembering all they had been through since the rout at Fredericksburg, I yearned to serve the dreariest of them all. |

Excerpt from Louisa May Alcott, Hospital Sketches (Boston: James Redpath, 1863). New-York Historical Society. Pg. 33-35.

Background

At the outbreak of the Civil War, nursing was not considered an appropriate activity for women. Most people believed that women were too weak and uneducated to endure the demands of working in a hospital.

In spite of this social prejudice, over 15,000 women traveled to hospitals and battlefields to volunteer as nurses during the Civil War. At the time, there were no nursing schools, so these women went into the field without training. They endured cruel treatment from male doctors and surgeons who hoped to discourage them.

Civil War nurses were responsible for duties far beyond the care of their patients’ bodies. They helped wounded and dying soldiers write letters home to their families. They talked to patients about physical and mental battlefield traumas, including the loss of limbs. They taught soldiers how to adapt to the physical limitations caused by their wounds. And they comforted the dying, making their passing as peaceful as possible. They performed these duties in addition to the laundering, sewing, and general housekeeping that was expected of all women regardless of the circumstances they found themselves in.

By the war’s end, these brave pioneers had overcome some of society’s biases and established nursing as a new career for women.

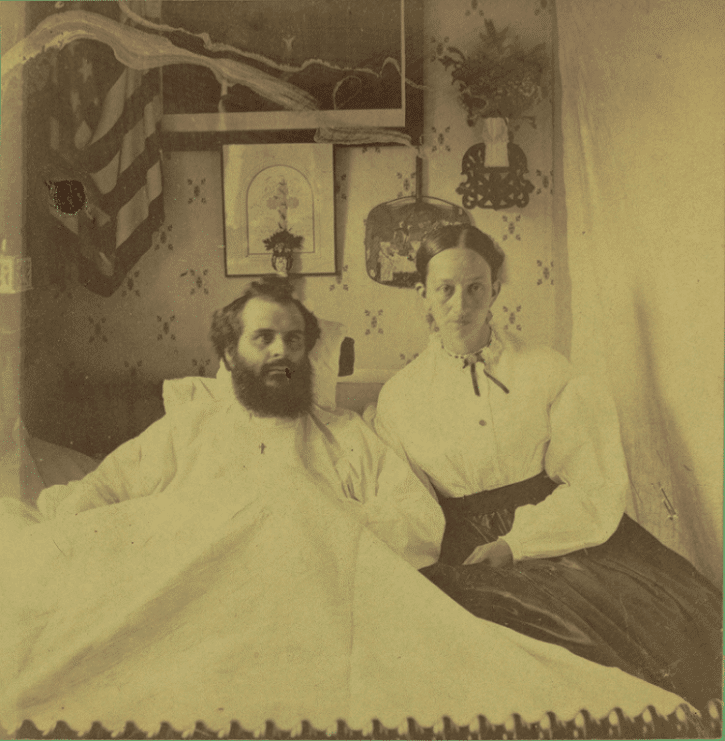

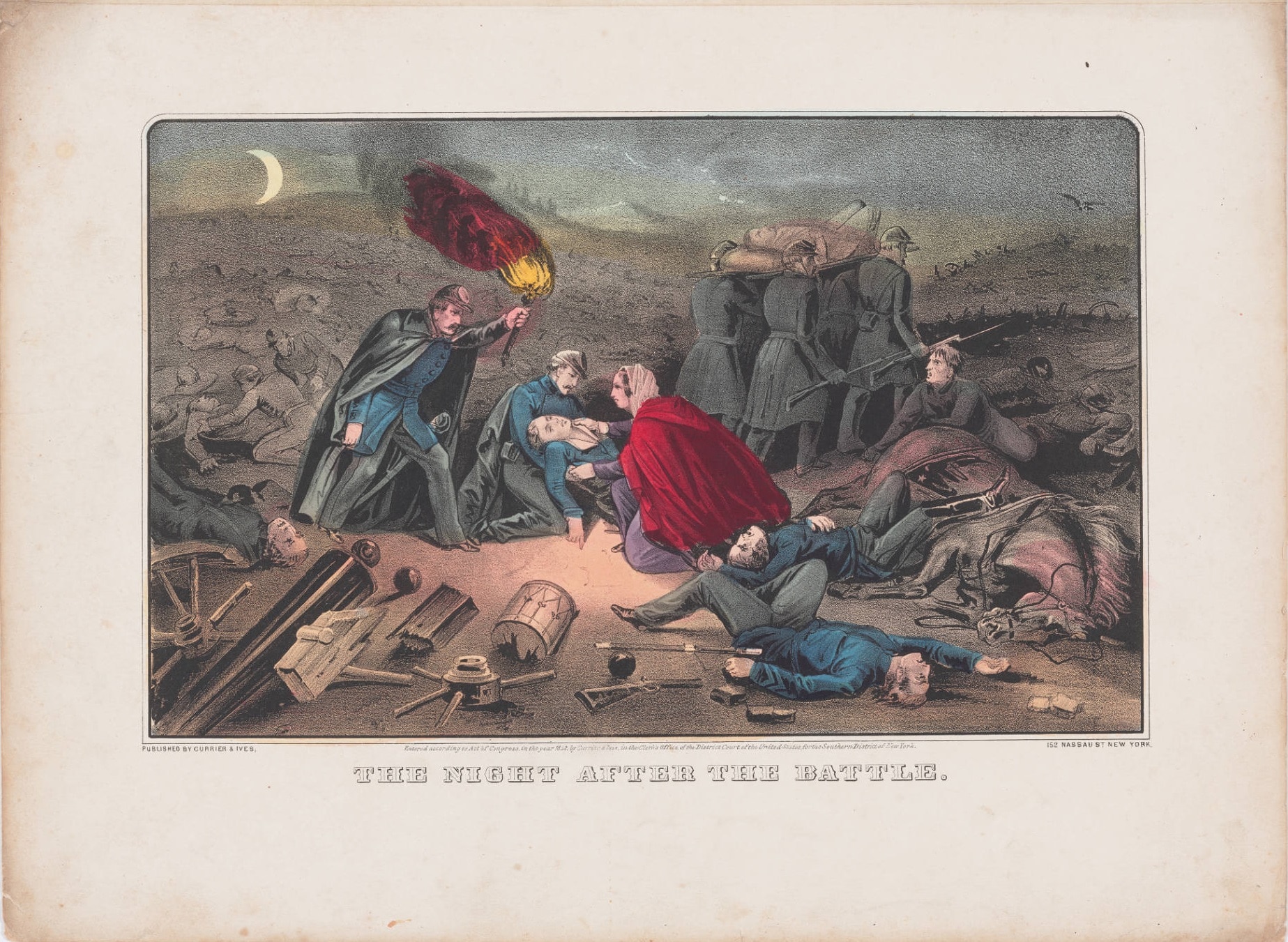

About the Image

These four sources illustrate the experiences of nurses during the Civil War. The photograph demonstrates the practical and somber clothing that all nurses were required to wear. The Currier and Ives print shows how the public attitude toward female nurses had shifted by mid-war from general disdain to something closer to hero worship. Sarah Blunt’s letter highlights the fact that communicable diseases were the most dangerous threat to the lives of soldiers and nurses. The excerpt from Louisa May Alcott’s Hospital Sketches recounts the first time the author encountered wounded troops straight from the battlefield.

Vocabulary

- admonished: Scolded.

- Burnside blunder: A mocking name for the terrible defeat that happened at the Battle of Fredericksburg. The blame for the defeat was placed on General Ambrose Burnside.

- christen: Give an official name.

- coal-hods: Buckets of coal.

- communicable disease: An illness that is easily spread from person to person.

- cordial draughts: Doses of medicine.

- drowsed: Slept.

- duly: According to procedure.

- engraving: A picture made from an engraved plate of metal or wood.

- fortitude: Strength.

- Fredericksburg: The Battle of Fredericksburg, December 13, 1862. Over 12,000 Union soldiers were killed or wounded in the battle.

- gaunt: Thin.

- matron: Head woman in charge of the ward.

- migratory: Moving.

- premises: Places.

- regiment: A unit of the army.

- rout: Defeat.

- rude: Handmade.

- scalded: Burned.

- shell: Bomb.

- tenanted: Occupied.

- vilest: Most disgusting.

- ward: Area of a hospital.

- yearned: Longed.

Discussion Questions

- What do these sources teach us about the experiences of women nurses during the Civil War?

- How did nurses like Sarah Blunt and Louisa May Alcott see themselves?

- Why do you think public attitudes toward women nurses changed so much over the course of the war?

Suggested Activities

- Include these sources in any lesson that explores life on the war front.

- To learn more about the heated debate over whether women nurses should be trained and professionalized, read the life story of Elizabeth Blackwell.

- To better understand the limitations placed on white middle-class women in this era and how women found ways to work around them, explore Abolitionist Crafts, Pro- and Anti-Slavery Literature for Children, Bleeding Kansas, Sanitary Fairs, and the life story of Sarah Moore Grimké and Angelina Grimké Weld.

- For a larger lesson about the ways women contributed to Union and Confederate war efforts during the American Civil War, teach these resources together with any of the following: Life Story: Sojourner Truth, Sanitary Fairs, Women’s War Production, Women Soldiers, Smuggling, Scenes from the Confederate Home Front, Changing the Rules of War, Life Story: Elizabeth Blackwell, Life Story: Emily Jane Liles Harris, Life Story: Loreta Janeta Velázquez, Life Story: Harriet Tubman, Swearing Loyalty, and Life Story: Susie Baker King Taylor.

Themes

SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY, AND MEDICINE