Louisa Smith spent her early life enslaved on a plantation in Washington County, Mississippi. She was part of a community of Black people who formed close bonds beyond their immediate plantation. These networks of kinship, made up of blood relatives, friends, and neighbors, were an important source of support for enslaved Black people living in the harsh realities of the antebellum South. Black women carefully tended and maintained these kinship networks, something Louisa learned at an early age.

Louisa married Israel Smith on Christmas Day in 1856. Because they were both enslaved, their marriage was not legally recognized. It also did not provide Louisa or Israel any protection from the whims of their enslavers. Their marriage was an act of hope and defiance, asserting a humanity that enslavers believed they did not possess.

When the American Civil War began in 1861, hundreds of Black men, women, and children left their enslavers and sought safety with the Union Army. This steady flow of refugees became a flood when Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation went into effect in January 1863. The Emancipation Proclamation freed all enslaved people in Confederate territories captured by the Union Army. Lincoln hoped that it would weaken the Confederate labor force and swell the ranks of the Union Army with ex-slaves eager to fight for their freedom. He failed to consider that Black women, children, and elders would also take their freedom. The Union military and government had no clear plan for what to do with Black noncombatants.

Louisa was one of thousands of enslaved women who took her own freedom in the spring of 1863. She and Israel set out together for the Union camps. Family and friends from their community in Washington Country accompanied them.

A Union gunboat on patrol in the Mississippi River picked up Louisa and Israel. The boat took them downriver to Louisiana. They quickly learned that the Union Army welcomed potential fighting men like Israel but saw Louisa as a nuisance. The boat stopped at Goodrich Landing, where Louisa was forced to disembark with the other women, children, elders, and infirm persons. Israel continued downriver to Lake Providence, where he enlisted with the 47th U.S. Colored Infantry (USCI) on May 1, 1863.

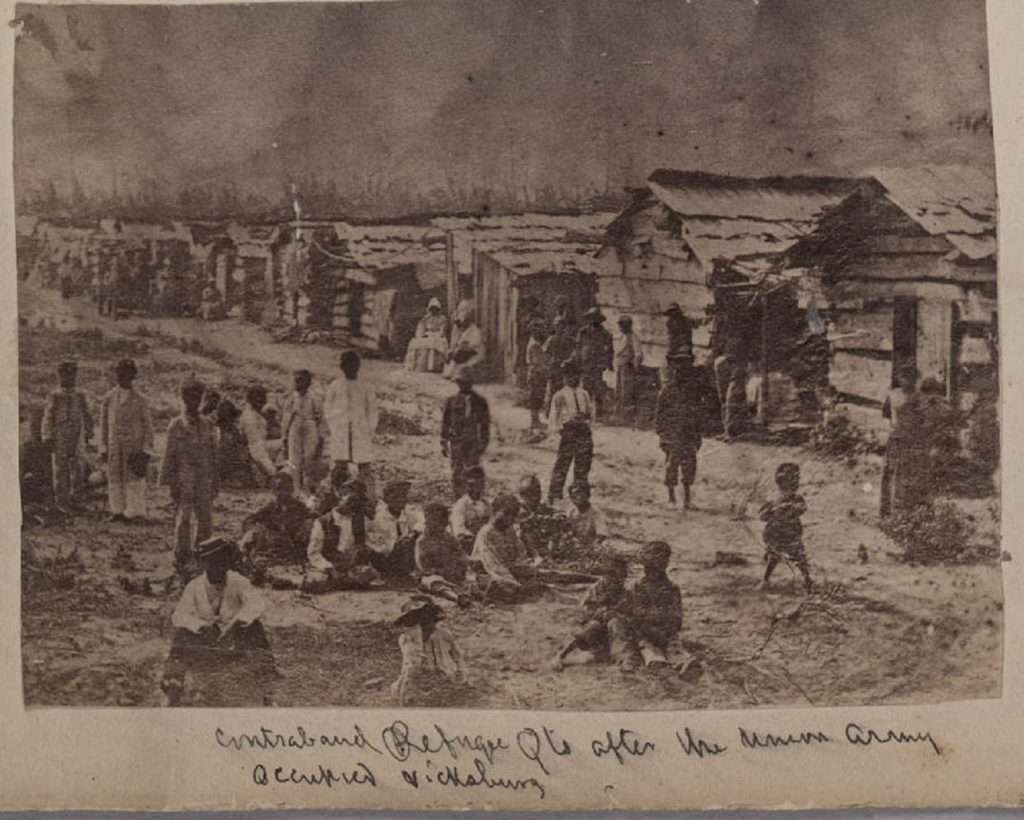

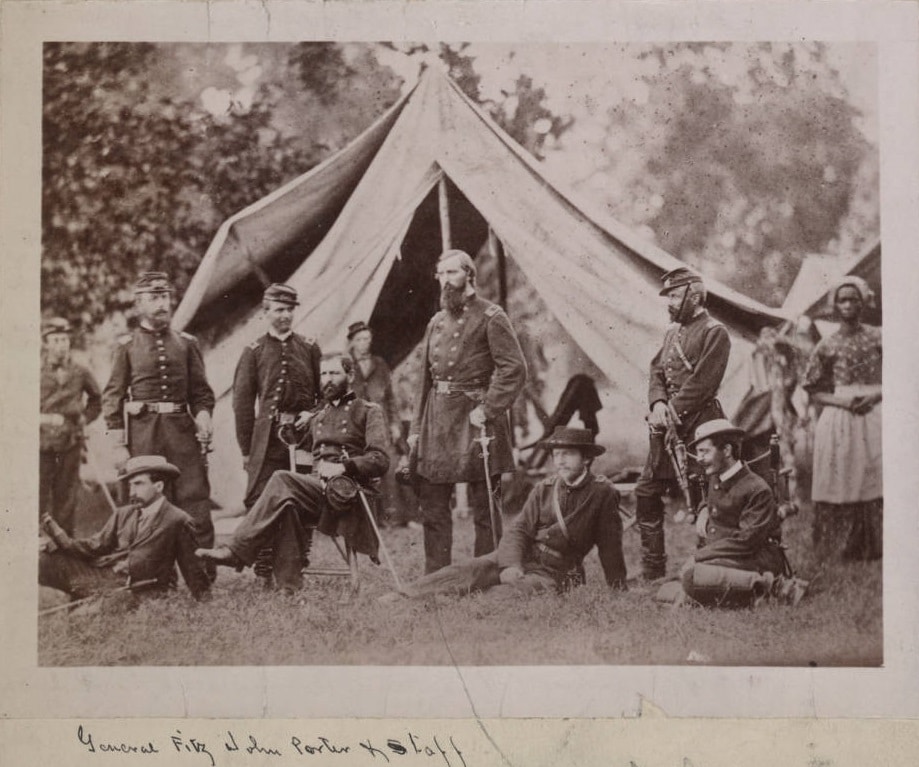

The Union Army that Louisa and the other refugees fled to struggled with how to meet this unexpected challenge. Early in the war, there was no official policy regarding formerly enslaved refugees, so Union commanders decided how to respond on an individual basis. Over time, the Union Army adopted a policy of labeling these refugees as contraband, war prizes that became the possession of the Army. But the Army did not have a set plan for how to protect and care for this vulnerable population. While Israel trained to fight the Confederacy, Louisa confronted the harsh realities of life as Union contraband. The U.S. government provided very little funding for the camps contraband were assigned to live in. Proper shelter, clothing, and food were scarce. The government leased abandoned plantations to Northern businessmen, who forced ex-slaves like Louisa to work on them. The workers were supposed to be paid but most never received payment.

Louisa was one of thousands of enslaved women who took her own freedom in the spring of 1863. She and Israel set out together for the Union camps.

The Union officers and soldiers who oversaw the contraband camps did not necessarily support the abolition of slavery. As long as the war continued, Louisa lived with the constant danger of being resold or captured and forced back into slavery. Even those who did support abolition were often eager to be rid of the refugees. They saw them as an unnecessary burden, which made returning the refugees to their enslavers a tempting option. Many Union soldiers also believed the dehumanizing stereotypes about Black people that were common in the antebellum period. This left refugees like Louisa in constant danger of physical or sexual assault. Conditions in some camps were so terrible that some refugees voluntarily returned to slavery to escape them.

Louisa and her friends from Washington County did what they had always done: worked together to ensure the survival of their friends and family. They took in children and infirm people who needed shelter, shared the meager resources they could acquire, and formed new networks of support to ensure everyone was cared for.

The camps where Louisa and other Black women were asserting their freedom and building new communities were vulnerable to attack. Louisa learned this firsthand at the end of June 1863, when Confederate troops attacked the camp at Goodrich Landing. The Confederates slaughtered many women and children. Others were captured and forced back into slavery. Louisa was among the lucky who scattered at the first sign of attack. She survived with her freedom intact.

In July 1863, Louisa learned that Israel was sick with dysentery. Her childhood friend Melinda Johnson dropped everything to support her during this crisis. The two women made their way to a hospital at Snyder’s Bluff, where they did everything they could to save Israel. When he died on July 27, only three short months after they first claimed their freedom, Melinda cared for Louisa on the trip back to Goodrich Landing. Louisa was met with love and support from her community. Many other women at Goodrich Landing had become widows in the short time since their self-emancipation. They understood her pain. More than a decade later, these women would come together again to support Louisa during the difficult process of claiming a widow’s pension from the U.S. government.

After Israel’s death, Louisa found work as a laundress for Company D, 50th USCI in Jackson, Mississippi. Domestic labor and nursing were the only forms of employment Black women could secure in the U.S. Army. During her work with the Company, she lived with soldier Charles Anderson. Historians do not know the nature of their relationship but staying with a soldier on the lines was considered more secure than living in the contraband camps. Unfortunately, this respite was short lived. Company D’s commanders ordered all Black women and children away from camp. When the soldiers responded by building nearby shelters, they were shut down. The message was clear. The Union Army was happy to take advantage of the labor of Black women, but wanted none of the responsibility of caring for their well-being.

Louisa made her way to Vicksburg, Mississippi. Union forces had captured Vicksburg in July 1863, and many Black refugees gathered there. They formed a community that became the foundation of a vibrant Black community that would continue to grow after the war. In 1867, Louisa returned to her former plantation as a free woman to reunite with her mother. She took work as a laundress there for a year before returning to Vicksburg. In Vicksburg, she supported herself by selling produce and chickens she raised. She supplemented her income by occasionally taking work as a day-laborer picking cotton. In 1874, Louisa filed for her widow’s pension. The files for her petition are the source for much of the information about her life. She disappears from public records after that date, so we do not know what happened to her.

Vocabulary

- abolition: Legal end.

- antebellum: Before the American Civil War.

- Confederate: Relating to the group of states that seceded from the United States before the Civil War in order to preserve slavery.

- contraband: The name the Union Army gave to all people who were liberated from slavery or escaped to Union lines during the American Civil War.

- dysentery: An infection of the intestines that causes severe illness and death.

- enlisted: Joined the armed forces.

- kinship: Familial relationship through birth or marriage.

- noncombatants: People who do not fight during a war.

- pension: A sum of money regularly paid to a former soldier for life in recognition of their service.

- Union: The name for the states that remained a part of the United States during the Civil War.

- United States Colored Infantry: The name for the volunteer Black troops during the American Civil War.

Discussion Questions

- Why did the Union Army treat Israel and Louisa differently?

- What hardships did Louisa face in the Union contraband camps?

- What does Louisa’s story reveal about attitudes toward Black women in the Civil War? Why do we need to understand this history?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 5.8 Military Conflict in the Civil War

- Include this life story in any lesson about the Emancipation Proclamation and its consequences for enslaved people in the Confederacy.

- Use this life story to illustrate the complicated history of Union contraband camps.

- Trace Louisa and Israel’s journey on a Civil War battle map to reveal how military campaigns affected Black Southerners.

- To give students context on what Louisa’s life on the plantation may have been like before the war, use the resources Plantation Slavery, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Resistance, and the life story of Anarcha, Besty, and Lucy.

- For an alternative story of a woman who became contraband during the American Civil War, read the life story of Susie Baker King Taylor.

- Read the life story of Harriet Tubman to learn about a Black woman who defied the Union Army’s expectations of gender and race.

- Taking their own freedom was one of many ways Black women could resist the institution of slavery in the United States. To learn more about Black women’s resistance, explore any of the following: Conditional Manumission, Women and the Code Noir, Fighting for Freedom in New Amsterdam, Elizabeth Jennings, Life Story: Elizabeth Freeman, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, Resistance, Life Story: Harriet Robinson Scott, Life Story: Sojourner Truth, Life Story: Harriet Tubman, Life Story: Susie Baker King Taylor, and Life Story: Elizabeth Keckley.

Themes

POWER AND POLITICS; AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP