Letters from Molly Nail, page 1

“Letters signed by Molly Nail,” February 20, 1832 and October 13, 1832, Correspondence on the Subject of the Emigration of Indians between the 30th November, 1831, and 27th December, 1833, with Abstracts of Expenditures by Disbursing Agents in the Removal and Subsistence of Indians (Washington: Printed by Duff Green, 1835). Library of Congress, A Century of Lawmaking For a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates 1774-1875, American Memory collections.

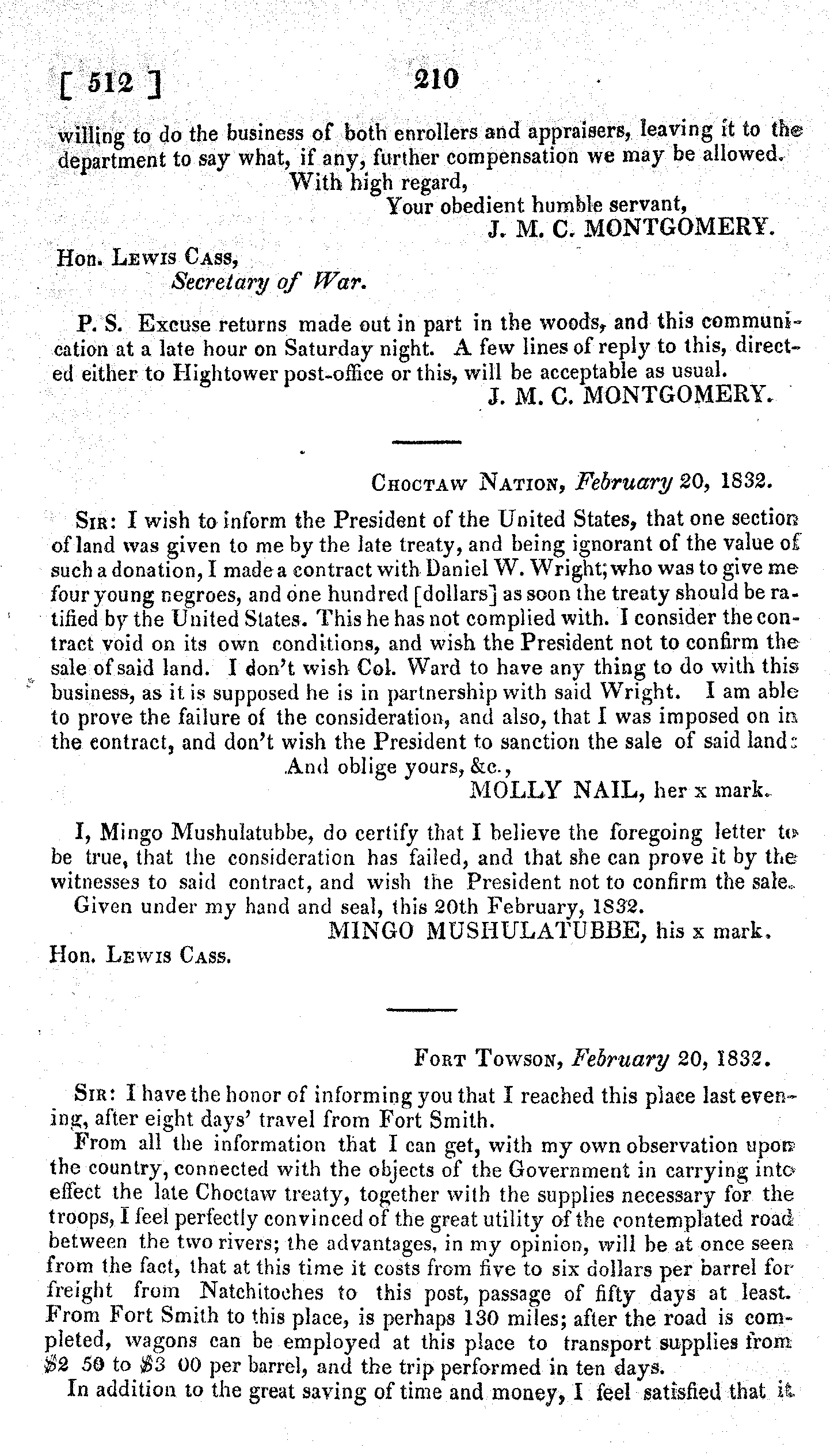

Letters from Molly Nail, page 2

“Letters signed by Molly Nail,” February 20, 1832 and October 13, 1832, Correspondence on the Subject of the Emigration of Indians between the 30th November, 1831, and 27th December, 1833, with Abstracts of Expenditures by Disbursing Agents in the Removal and Subsistence of Indians (Washington: Printed by Duff Green, 1835). Library of Congress, A Century of Lawmaking For a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates 1774-1875, American Memory collections.

Document Text |

Summary |

| CHOCTAW NATION, February 20, 1832. | Choctaw Nation, February 20, 1832 |

| Sir: I wish to inform the President of the United States, that one section of land was given to me by the late treaty, and being ignorant of the value of such a donation, I made a contract with Daniel W. Wright; who was to give me four young negroes, and one hundred [dollars] as soon the treaty should be ratified by the United States. This he has not complied with. I consider the contract void on its own conditions, and wish the President not to confirm the sale of said land. I don’t wish Col. Ward to have any thing to do with this business, as it is supposed he is in partnership with said Wright. I am able to prove the failure of the consideration, and also, that I was imposed on in the contract, and don’t wish the President to sanction the sale of said land: | I want to tell the President of the United States that I received one portion of land through the treaty. I did not know the land’s worth so I made a deal with Daniel W. Wright. He was supposed to give me four enslaved people and $100 once the treaty is accepted. He has not held up his side of the deal. The contract is void and I want the President to not accept the deal. I do not want to deal with Colonel Ward or Wright. I can prove that the contract was not completed, and do not want the President to okay the deal. |

| And oblige yours, &c., MOLLY NAIL, her x mark. |

Sincerely, Molly Nail |

| I, Mingo Mushulatubbe, do certify that I believe the foregoing letter to be true, that the consideration has failed, and that she can prove it by the witnesses to said contract, and wish the President not to confirm the sale. | I, Mingo Mushulatubbe, can confirm the truth of this letter and that the contract was not fulfilled. I also want the President not to okay this deal. |

| Given under my hand and seal, this 20th February, 1832. MINGO MUSHULATUBBE, his x mark. |

Given honestly and truthfully, Mingo Mushulatubbe |

| CHOCTAW AGENCY, October 13, 1832. | Choctaw Agency, October 13, 1832 |

| Sir: I am now about to leave for my new country west of the Mississippi. Colonel Wright and Samuel Ragsdale have settled and paid me in full for my section of land given me by the treaty. I have heretofore objected to the bargain made with Colonel Wright, but as Colonel Wright and Samuel Ragsdale have paid me in money and negroes, and I do now wish and desire that a title may be made to them, and that the President will ratify and consent to the trade. The bargain was made in the presence of William Armstrong, superintendent for our removal, who has seen the negroes that were paid me. I am now satisfied, and willingly withdraw any objections I ever made to Colonel Wright’s having a title made him.

|

I am about to leave for new land west of the Mississippi. Colonel Wright and Samuel Ragsdale have paid me the total amount for the land. I want to cancel the claims I made in my previous letter. I want to move forward with the sale of the land with Colonel Wright and Samuel Ragsdale since they have paid me in money and enslaved people. I ask that the President accept that sale. The deal was made and witnessed by William Armstrong, the supervisor of our removal, who also saw the enslaved people I was paid with. I am now satisfied. I remove my former claim against the purchase with Colonel Wright. |

| I now desire to have the title made to Colonel Wright and Samuel Ragsdale. | I want the title to be given to Colonel Wright and Samuel Ragsdale. |

| Respectfully, your obedient servant, MOLLY NAIL, her x mark. |

Sincerely, Molly Nail |

“Letters signed by Molly Nail,” transcription, February 20, 1832 and October 13, 1832, Correspondence on the Subject of the Emigration of Indians between the 30th November, 1831, and 27th December, 1833, with Abstracts of Expenditures by Disbursing Agents in the Removal and Subsistence of Indians (Washington: Printed by Duff Green, 1835). Library of Congress, A Century of Lawmaking For a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates 1774-1875, American Memory collections.

Background

Choctaw people began buying, selling, and owning enslaved Black people in the late 1700s. Choctaw slave owners recognized that owning and exploiting enslaved people gave them economic power in the United States.

In the early 1800s, the Choctaw Nation became a target of the U.S. government, which wanted to give Choctaw lands in Mississippi to white settlers. In 1830, Choctaw leaders were forced to sign the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek with the U.S. government. Choctaw people were forced off their lands for new territory west of the Mississippi River. When the Choctaw moved westward, they brought their enslaved people with them.

Choctaw people who privately owned land east of the Mississippi River sold it to white buyers in exchange for cash and enslaved people, turning their land into wealth that could be transported with them to their new lands. The enslaved Black men, women, and children forced to travel west with their owners had no say in their fate. They lost ties to the families and communities they had known in the Deep South.

About the Document

In these two letters, Choctaw woman Molly Nail writes to the U.S. government twice to give updates about the sale of her land after the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek. In the first letter, she is angry because she has agreed to sell her land to an agent for four enslaved people and $100, but she has not yet received payment. She asks the government to stop the sale. In the second letter, she writes that her payment has been received and she wants the government to approve it.

Each letter ends with “Molly Nail, her x mark.” This implies that Molly could not read or write. Interpreter John Pitchlyn transcribed her letters, and she signed them with an x.

Vocabulary

- chattel: An item of property other than real estate.

- Choctaw: The Choctaw are a Native community who originally inhabited territory spanning Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, and Louisiana before U.S. expansion westward. Today, the Choctaw Nation is centered in Mississippi.

- consideration: Agreement.

- heretofore: Previously.

- ratify: Confirm.

- sanction: Confirm.

- title: Deed.

- void: Not legal.

- x mark: A notation that indicates someone signed with an “x” because they could not write their name.

Discussion Questions

- Why would Choctaw people sell their land in exchange for enslaved people before heading west?

- What do these documents reveal about the role of enslaved people in Indian Removal?

- Why is it important to acknowledge the history of slavery in Native nations?

Suggested Activities

- Include these documents in a lesson about Indian Removal to expose students to the history of slavery in Native communities.

- Invite students to do research about the history of chattel slavery in Native communities. Which tribes adopted the practice? Which tribes did not? How did Native communities respond to the end of slavery in the United States?

- Combine these documents with the Sarah Watie letter for a larger lesson about how Native communities were impacted by slavery and the American Civil War.

- Like the U.S. government, Native governments had to determine the citizenship status and rights of free Black people in their communities after the war. Tensions over these issues still continue today. Read here to learn more, and invite students to consider how this ongoing battle in Native communities mirrors the ongoing conversation about race and citizenship in the United States.

Themes

AMERICAN IDENTITY AND CITIZENSHIP