Background

The debate over slavery in the United States began to dominate national politics in the 1830s and 1840s. Pro-slavery advocates as well as abolitionists started to print books and pamphlets made specifically for children. Both sides hoped that they were raising a new generation of supporters who accepted their arguments as established truths.

In the 1800s, women were responsible for the moral education of children. Writing books for children was an accepted way women could publicly share their political opinions.

About the Document

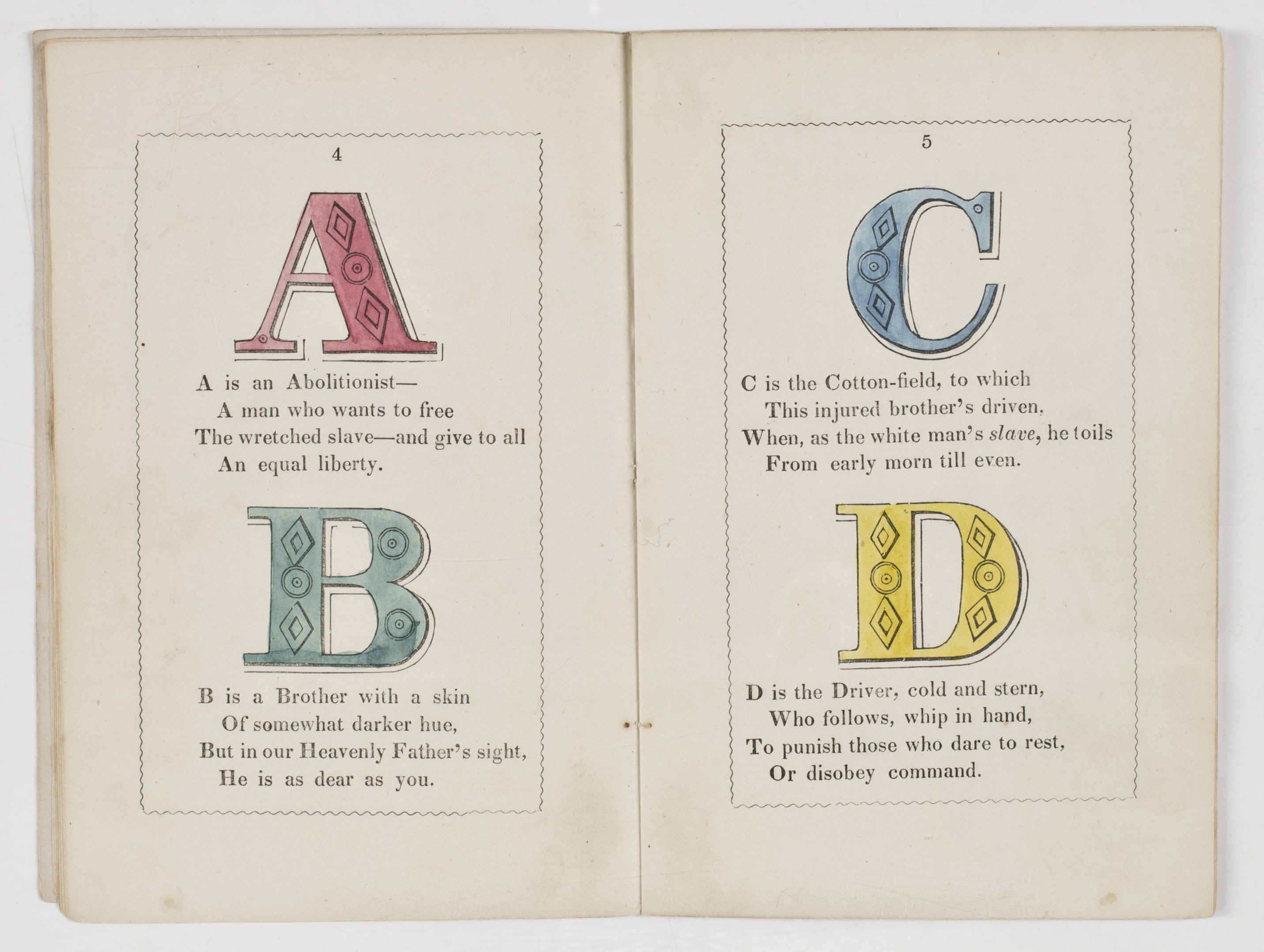

Hannah and Mary Townsend, two Quaker sisters who belonged to the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society, wrote The Anti-Slavery Alphabet. They wrote the book for a very young audience. They hoped that parents would use it to teach their children to recognize their letters and support the abolitionist movement. It was first sold at the 1846 Philadelphia Anti-Slavery Fair.

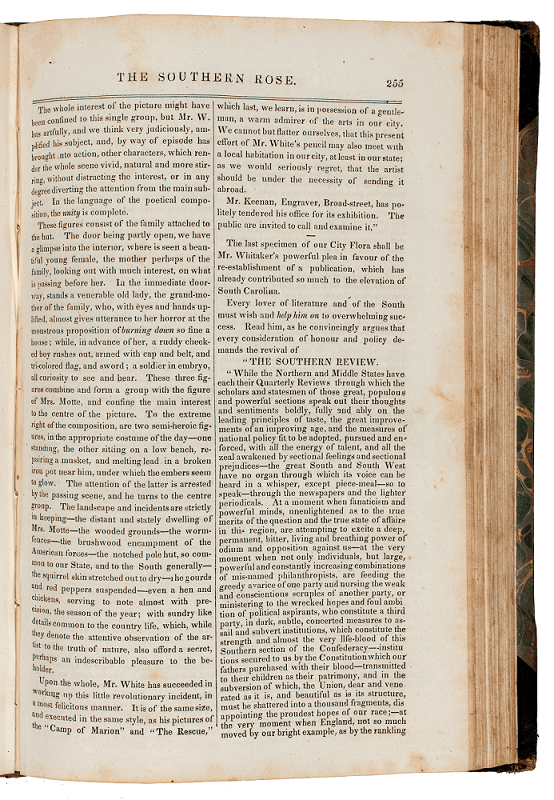

The Southern Rose (also called The Rose Bud and The Southern Rosebud) was a literary magazine for children written by Caroline Howard Gilman. The magazine was published from 1832 to 1839. Gilman was a Northern woman who moved to Charleston, South Carolina, with her husband and fully adopted the Southern way of life. She believed that slavery was a natural and beneficial part of American culture. She gave her young readers advice for how to best manage enslaved people. She also wrote negative reviews of abolitionist children’s literature. In this piece, she tells her young readers to be careful when reading publications from Northern states that seek to end slavery and destroy the Southern way of life.

Vocabulary

- abolitionist: A person or group that wanted to end the practice of slavery.

- aspirants: Hopefuls.

- assail: To attack.

- avarice: Extreme greed.

- concerted: Intensive.

- Confederacy: Country.

- constitute: Make up.

- odium: Hatred.

- organ: Magazine.

- patrimony: Heritage.

- philanthropists: People who give money to charitable causes.

- piece-meal: A little at a time.

- propaganda: Information used to promote a particular political view.

- Quaker: A Christian religious group founded in the 1650s. Quakers were early advocates for ending slavery in the United States.

- Quarterly Reviews: Magazines about books, politics, and philosophy.

- scruples: Doubts.

- sectional: Geographical.

- subvert: Undermine.

- zeal: Enthusiasm.

Discussion Questions

- What advice do Hannah and Mary Townsend give very young abolitionists?

- What Southern institution is Caroline Howard Gilman so anxious to defend? How does she describe the importance of this institution?

- Why did all three of these authors write for young people?

- What can you learn about the antebellum debate over slavery by comparing and contrasting these pieces?

Suggested Activities

- APUSH Connection: 5.5 Sectional Conflict: Regional Differences

- Use these documents to demonstrate how Americans of all ages were engaged in the slavery question in the antebellum period.

- Teach these documents together with the abolitionist crafts, Bleeding Kansas, Ad for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and the life story of the Grimké Sisters for a larger lesson about the many ways white women took action in the antebellum slavery debates.

- Compare Caroline Howard Gilman’s idealistic ideas about slavery with the realities represented in the resources Plantation Slavery, Life Story: Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy, Urban Slavery, Life Story: Sojourner Truth, Life Story: Harriet Tubman, and Life Story: Elizabeth Keckley.

- To see how the idea of slavery taught by Caroline Howard Gilman influenced the thinking of Southern white slaveholders, even after the end of the Civil War, read Life Story: Ella Gertrude Clanton Thomas.

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE; AMERICAN CULTURE; DOMESTICITY AND FAMILY