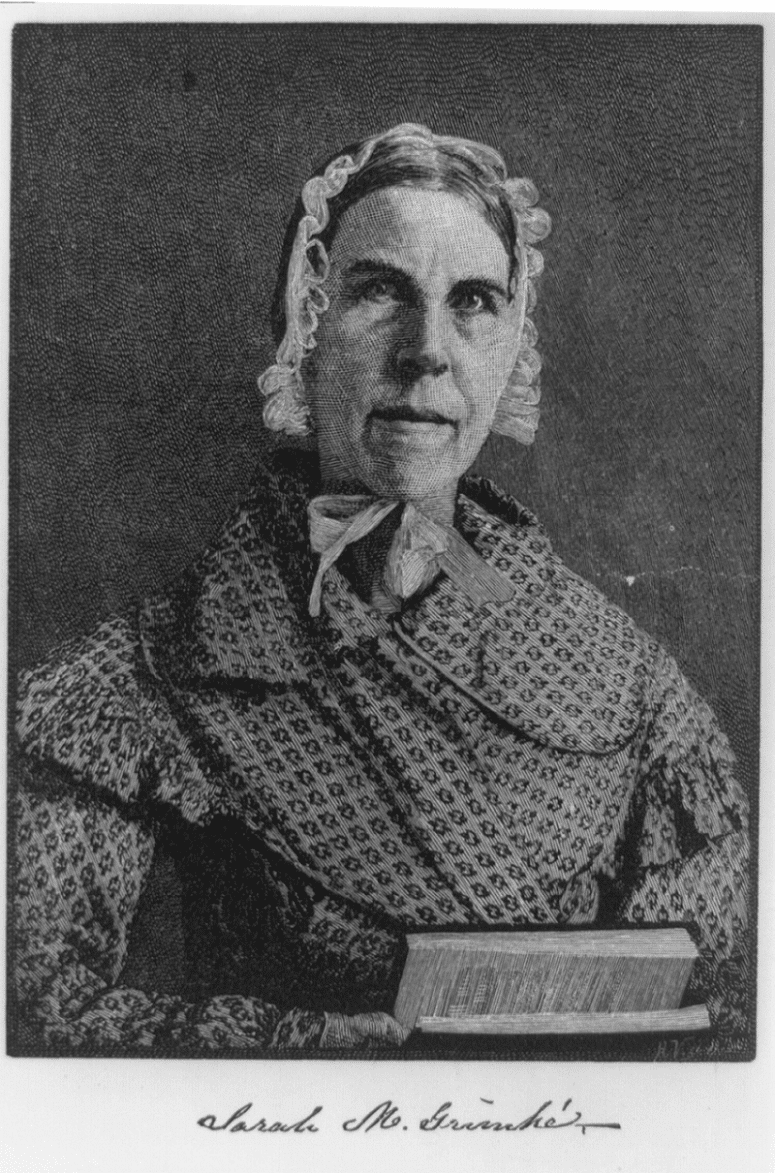

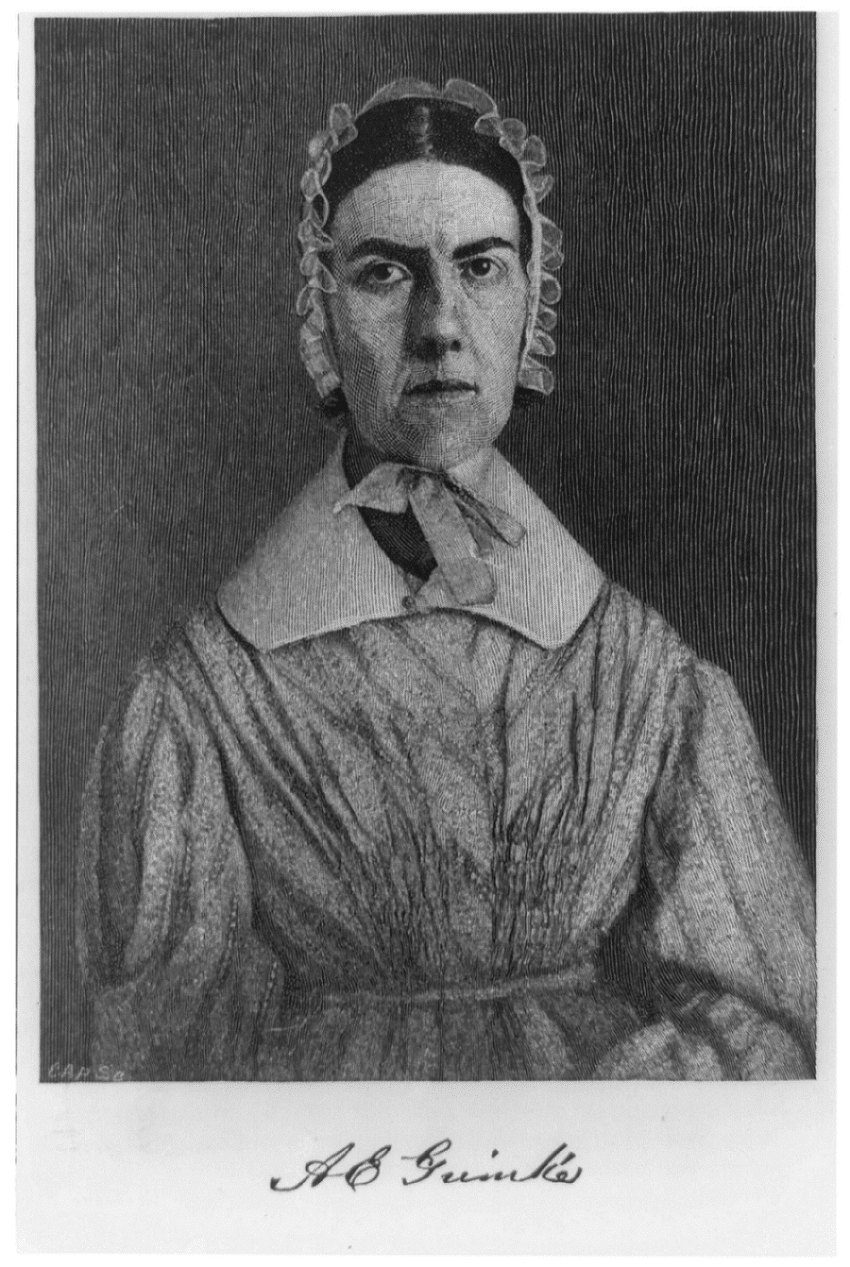

Sarah Moore Grimké and Angelina Grimké Weld were born in Charleston, South Carolina. Their father, John Facheraud Grimké, owned many enslaved people. Their mother, Mary Grimké, was the daughter of a wealthy and powerful plantation-owning family. Although Sarah was 13 years older than Angelina, the two sisters were very close.

John Facheraud Grimké believed that women should be subordinate to men, so while he provided an excellent education for his sons, he did not do the same for Sarah and Angelina. This did not stop both girls from growing up curious about the world around them. Through their own studies, they grew to reject the beliefs of their parents. They thought that women should be given the same rights as men and that slavery was an evil practice that needed to be abolished. Angelina was particularly outspoken, which got her in trouble with her family and community.

When Sarah was in her twenties, she grew tired of the limited scope of her life in Charleston and began to make regular visits to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. On these trips, she became acquainted with the Society of Friends, more commonly known as the Quakers. The Quaker community was more tolerant of women’s rights than most groups in the early 1800s, which must have appealed to Sarah. They were also supporters of the abolitionist movement. Sarah moved to Philadelphia and permanently converted to Quakerism in 1821. Angelina joined her in 1829.

Angelina soon became frustrated with the limited anti-slavery activities of the Society of Friends in Philadelphia. She wanted to take more direct action. So she joined the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society and took out a subscription to William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator. Sarah was concerned about Angelina’s new interest in the more radical kinds of abolitionism taking hold in the North, but she agreed with her sister that more direct action was needed. In 1835, Angelina wrote a letter to The Liberator expressing her beliefs. William Lloyd Garrison was so impressed with the letter that he published it in his newspaper. Abolitionists from all over the country praised her passion and eloquence, but the Quaker community of Philadelphia condemned her for stepping outside the bounds of modest female behavior.

By 1836, Sarah and Angelina were both publishing abolitionist writings. Many praised the power of their writing, but not everyone supported them. Sarah and Angelina wanted to advance the causes of abolition and women’s rights at the same time. Many abolitionists were uncomfortable with the idea of women achieving political and social equality. Likewise, many women’s rights advocates were not comfortable with abolishing slavery. This made Sarah and Angelina outsiders in both communities.

Sarah and Angelina wanted to advance the causes of abolition and women’s rights at the same time. Many abolitionists were uncomfortable with the idea of women achieving political and social equality.

Angelina and Sarah were invited to speak publicly to a group in New York City in the fall of 1836. This launched a new phase of their activist careers. The sisters traveled all over the Northeast giving talks on abolition and women’s rights. Their perspectives on the question of slavery were highly valued because they had grown up in a slave-holding family and understood the system more intimately than most Northern abolitionists. Angelina was considered one of the most powerful speakers in the abolitionist movement. In 1838, she became the first American woman to address a legislative body when she spoke about abolition and women’s rights in front of the Massachusetts state legislature.

But as the Grimké sisters’ fame spread, a backlash against them grew. Many people were unhappy to see women taking a public role in social and political debates. They felt Sarah and Angelina were stepping too far outside of the behavior of “respectable women.” People were particularly angry that Sarah and Angelina spoke in front of audiences that included both men and women and Black and white people. A group of ministers wrote that it violated God’s order and was “unnatural.” But the sisters believed they were doing God’s work. They defended a woman’s right to speak against slavery and continued to do so themselves.

On Monday, May 14, 1838, a four-day abolitionist convention began in Philadelphia. It was the first event in Pennsylvania Hall, which had been built by abolitionists because their unpopular cause made it difficult to rent meeting space. That night Angelina married fellow abolitionist Theodore Weld. Both Black and white abolitionists were in attendance.

On Wednesday, May 16, Angelina gave a speech to the convention. That evening, a noisy anti-abolitionist mob had gathered outside the building. The mob interrupted her several times. They threw rocks through the windows. This mob of Northern whites was particularly angry because Black abolitionists were present at the meeting. They screamed insults and threw more rocks when Black and white women left the building arm in arm. On Thursday, after the mayor canceled the convention to restore peace, the mob broke into the empty building and set it on fire. Firefighters allowed the structure to burn to the ground.

Sarah and Angelina moved to New Jersey with Angelina’s husband, Theodore. They continued to write and support the abolitionist cause, but they never took such a prominent role in the movement again. Together with Theodore, the sisters opened and ran schools in Belleville and Perth Amboy, New Jersey, before moving to Massachusetts in 1863.

In 1868, Sarah and Angelina learned that their brother, Henry, had fathered three children with one of the women he enslaved. They welcomed the children into their family and personally paid for their education. The two eldest nephews became civil rights activists, following in their respected aunts’ footsteps.

Vocabulary

- abolitionist: A person or group that wanted to end the practice of slavery.

- convention: A large, multi-day meeting.

- legislative body: The group of people who make and amend laws in a state or country.

- Society of Friends: A Christian religious group founded in the 1650s, more commonly known as Quakers. Quakers were early advocates for ending slavery in the United States.

- women’s rights: The cause of promoting women’s equality to men.

Discussion Questions

- How did Sarah and Angelina’s childhood shape their careers as activists?

- Why were Sarah and Angelina considered too radical by both the abolitionist and the women’s rights communities?

- What does Sarah and Angelina’s story reveal about the limitations placed on women in the nineteenth century?

Suggested Activities

- Include this life story in any lesson about prominent leaders of the abolitionist movement.

- For a larger lesson about how white women participated in the antebellum debate over slavery, combine this resource with the life story of Abolitionist Crafts, Ad for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and Pro- and Anti-Slavery Literature for Children.

- After reading this story, invite students to learn more about the experiences of Black women anti-slavery activists in the antebellum period, and compare and contrast the challenges and experiences of each: Elizabeth Jennings, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Salem Female Anti-Slavery Society, Resistance, Harriet Robinson Scott, and Sojourner Truth.

- Explore “All Bound Up Together” to learn about how the abolition and women’s rights movements pivoted after the end of the Civil War.

- Angelina and Sarah personally funded the education of their Black nephews to give them advantages in life. To learn more about the importance of education in the Black community, read the life story of Susie Baker King Taylor.

Themes

ACTIVISM AND SOCIAL CHANGE

New-York Historical Society Curriculum Library Connections

- For more on women activists in the early nineteenth century, see Saving Washington.